Trees and vegetation

There are many benefits from planting trees or restoring woody vegetation on a farm, including to help combat climate change by absorbing carbon dioxide. The Emissions Trading Scheme provides a way for forest owners to be rewarded for this sequestration, but it's a complex process.

If you are considering forestry on your farm for carbon sequestration, make sure you get advice from a qualified forestry expert, an ETS adviser and/or Te Uru Rākau/Forestry New Zealand.

Sequestration in vegetation

Sequestration in a forestry context is the process of woody vegetation (e.g. trees) removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as it grows. The carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere is stored as stable cable in the tree (e.g. trunk, branches) and becomes designated as a carbon sink.

When vegetation is removed, for example by harvesting or burning, it can become a source of emissions.

While pastures and crop also remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, this is released when they are eaten by animals and/or humans, which occurs over relatively short timeframe (weeks and months). They are not a sink for stable carbon that accumulates year-on-year, unlike the carbon in growing woody vegetation.

The amount of carbon that different vegetation types sequester is finite. This is because once they reach maturity, they tend to be losing as much carbon as they are gaining, i.e. at equilibrium or steady-state.

Forestry and the Emissions Trading Scheme

The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) provides a way for owners of newer forests to be rewarded for the carbon dioxide stored through photosynthesis by their forests as they grow.

Definition of a forest in the ETS

The ETS has a specific definition for what a forest is, known as the 'forest land definition'. This is to differentiate between land managed as a forest and other trees in the landscape. For a forest to qualify for the ETS, it needs to be:

- At least 1 hectare or more of forest species (a 'forest species' can grow to at least 5m in height at maturity where it is located, and can be planted or regenerated)

- Able to achieve tree canopy cover of at least 30% in each hectare at maturity

- Able to achieve an average tree canopy width of at least 30m at maturity

Wide-spaced poplar pole planting can meet the definition of a forest in the ETS if it will achieve at least 30% canopy cover in each hectare at maturity.

The current definition excludes:

- Shelterbelts (unless they are wider than 30m)

- Fruit trees and nut crops

- A forest that existed before 1990

Small forest plantings and riparian strips are also excluded. However, the Government is looking at on-farm sequestration as part of its development of a farm-level pricing mechanism for agricultural greenhouse gas emissions.

Classes of forest

Forest land is classified differently in the ETS depending on when it was first established.

The Kyoto Protocol set 1 January 1990 as the international baseline date for net emissions. Forests established before this date (and that were in exotic forest on 31 December 1989) are called 'pre-1990 forests' and are considered part of New Zealand's baseline emissions and removals. They can't be counted as additional carbon storage in the ETS.

Exotic pre-1990 forests can be harvested and replanted without penalty. If the forest is converted to another land use or the forest is not re-established, carbon credits will need to be paid for the equivalent amount of carbon stored in the forest. This can come at a substantial cost to the landowner, depending on the carbon price of the day.

Bay of Plenty sheep and beef farm with a mix of restoring native bush and plantation forestry (Credit: Dave Allen Photography)

Forests established (planted or regenerated) after 31 December 1989, or 'post-1989 forests', are considered new carbon sinks and can be registered with the ETS to earn carbon credits. Any credits claimed must be paid back if the forest is converted to another land use or removed from the ETS.

If the forest was established after 1989 and hasn't been registered with the ETS, then no carbon credits can be claimed and no carbon liability is payable if the forest is converted.

If you're embarking on a forestry project, have a look at www.canopy.govt.nz, a Te Uru Rākau website covering all stages of forestry from planting to harvest, including information on ETS considerations.

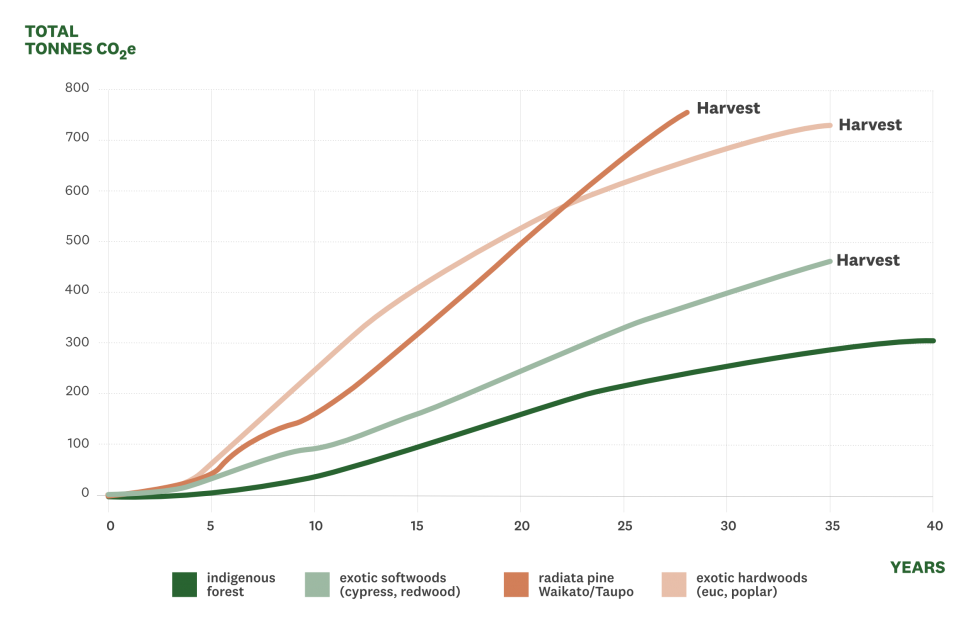

Rates of sequestration between species

Different species sequester carbon at different rates, as shown in the figure below. The Ministry for Primary Industries issues standardised 'look-up' tables to assess carbon sequestration. ETS participants that have less than 100 hectares of registered ETS forest must use these tables to work out the carbon stored in their forest. ETS participants with 100 hectares or more must physically measure the carbon stock in their forest.

More work is being done to improve the accuracy of look-up tables for species other than pine. These all currently use national averages. For more, see here.

Earning carbon credits with forestry

The way ETS participants account for their carbon and earn credits from their forests has changed as from 1 January 2023.

'Averaging accounting'

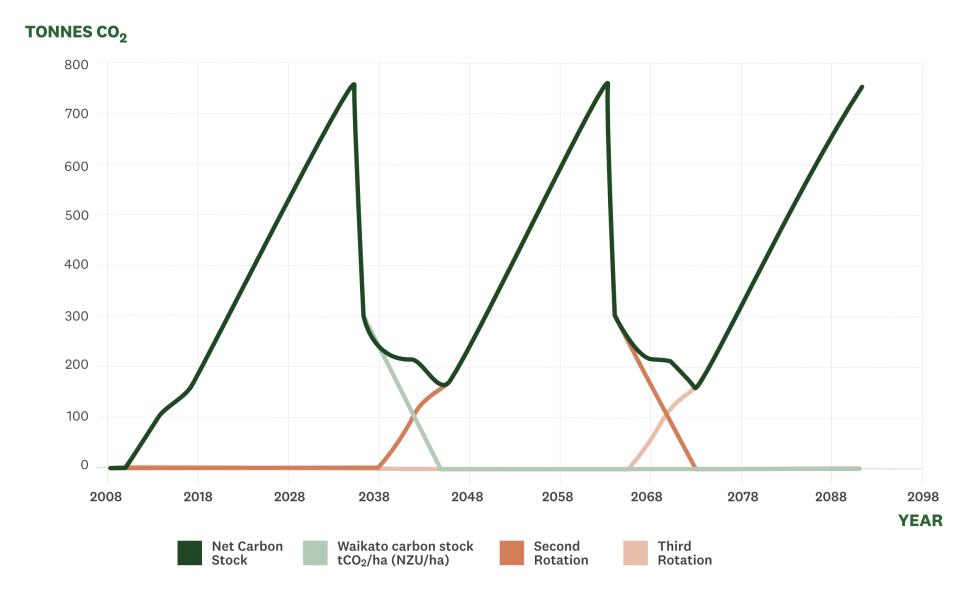

Instead of accounting for the actual increases and decreases in carbon, participants now account for the long-term average amount of carbon stored in the forest. This is illustrated by the shaded areas in the figure below.

Participants will earn credits on their first rotation until their forest reaches its average long-term carbon stock, which has been estimated over several rotations of growth and harvest.

The average carbon stock of a forest will depend on the species and when that type of forest is typically harvested. MPI has set 'average years' for different species:

- Pines - 16 years

- Douglas Fir - 26 years

- Exotic softwoods, e.g. cypress, redwood - 22 years

- Exotic hardwoods, e.g. eucalypt, poplar - 12 years

- Natives - 23 years

Once the forest reaches its average carbon stock, it will stop earning credits. When it is harvested, these credits won't need to be repaid to the Government. Participants will only earn additional credits or need to pay them back if the forest is harvested significantly earlier or later than usual, or is deferred/de-registered.

This regime would apply to all production forests that will be harvested.

For more details on averaging, talk to a forestry/ETS consultant or Te Uru Rākau/Forestry New Zealand.

Permanent foresty activity

The second option, as from 1 January 2023, is as a new permanent forestry activity. This applies to forests that are not intended for harvest.

Forests in the permanent category will use the stock change approach (see below) and will earn carbon credits for as long as the forest is in the ground and the carbon stock is increasing.

The minimum term for the permanent category is 50-years, during which the forest can't be clear-felled (although selective harvesting is allowed if the forest doesn't drop below 30% canopy cover).

Once the 50-year period is ended, the forest can either remain as permanent forest or move to the averaging approach or can leave the ETS. Credits would need to be surrendered for the last two options.

Owners will be able to have a mix of 'permanent' and 'standard' post-1989 forest land.

Stock change accounting

Initially, to earn carbon credits ETS participants had to 'account' for the increases and decreases in carbon in their forests.

They did this by accounting for the short-term changes in the carbon stored in their forest (called 'stock change' accounting). This follows the pattern in the graph below.

As the forest grows and stores carbon, the ETS participant can earn carbon credits from the Government that they can keep or sell on the carbon market.

When the trees are harvested, approximately 60-70% of the carbon leaves the land. The remaining carbon, tied up in the stumps, roots and slash, slowly decays away over a period of 10-years. These emissions are effectively offset by the carbon sequestration in the newly planted next rotation.

If the forest wasn't replanted, the carbon stock would eventually return to zero, and all the carbon credits earned would need to be repaid.

If the forest is replanted, the new growth from the second rotation will overtake the decay from the previous rotation and the forest will begin earning credits again. This is usually about 8-10 years after harvest.

Under the permanent forestry regime, using the 'stock management' approach, forest owners can claim carbon credits for as long as the forest is growing. It could potentially be for hundreds of years, before the forest reaches an equilibrium state.

Offsetting emissions with forestry

Establishing a new forest and registering it with the ETS is a useful way to earn additional income from carbon credits and the sale of timber or other forest products. The new forests could help offset some of the costs soon to be faced with on-farm emissions pricing.

It is important to note that carbon credits from an ETS forest can either be sold or used as an offset for on-farm emissions. It cannot be used for both as that would be double-counting. To claim an offset with forestry, the sequestration cannot be used elsewhere.

Solely using forestry to offset farm emissions may be difficult to achieve for the average farm. Production forests (under the averaging regime) will offset emissions for a period of time, but once they reach their 'averaging' age, no further credits can be claimed. Additional areas will then need to be planted to continue offsetting and earning credits. Assuming no other mitigations are used (e.g. emissions are not reduced), an ever-increasing area is required for replanting, as shown in the table below.

Replanting required for pines under averaging approach, if used as the sole emissions offset:

| Year 1 | Year 17 | Year 34 | Year 51 | Year 68 | |

| Plant (ha) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Total (ha) | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 |

What the above table shows is that, assuming 10ha is sufficient to offset the farm's emissions, after 16 years, no more carbon credits can be claimed so another 10ha must be planted, and so on.

The next table illustrates the area of forestry required to offset the average farm's greenhouse gas emissions, depending on the percentage offset required and based on how the ETS averaging approach might work.

Area of forestry required to offset, using the averaging scheme:

| % offset* | 5% | 10% | 25% | 50% | 100% |

| 155ha dairy farm | 3.7 | 7.4 | 18.5 | 37.2 | 74.4 |

| 695ha sheep & beef farm | 6.3 | 12.5 | 31.3 | 62.6 | 125.1 |

*Table is based on the national average Pinus radiata data. Regions and other species will vary. The average taken gives a 16-year offset.

The main points to remember are:

- The forest must be replanted, otherwise the full amount of carbon credits that were claimed must be repaid; and

- The benefit of 'low risk' credits only applies to newer production forests and permanent forests.

Indigenous forestry

There are pros and cons when considering indigenous species for forestry offsetting. Indigenous species sequester around 20-30% of carbon per year compared with pines. However, they sequester it for 200-300 years.

Indigenous species can be very expensive to establish, e.g. $10,000-$40,000/ha in comparison to pines at around $2,500-$3,000/ha. But they can also bring significant biodiversity benefits.

Forestry in the farm system

Forestry provides a potential opportunity to diversify on-farm income through timber and carbon.

Like any land use, it is important to consider how that land use will work within the farm system. Identifying the best place to plant, or regenerate vegetation is important. If forestry is going to be harvested for timber then there are several on-farm infrastructure requirements that will need to be met, e.g. roading.

It is also important to identify what other objectives need to be met. For example, you may be able to enhance biodiversity, manage erosion risk, or enhance stream health with the right sort of planting as well as increasing carbon sequestration.

Strategic use of tree planting or regeneration in a farm system may also help to achieve a reduction in stocking rate, improved per animal performance and improved overall profitability for a business.

It is important to get good advice on planting the right tree in the right place for the right purpose.

More information

For more information on forestry and the ETS, see MPI's forestry webpages. The topics addressed in this part of the Ag Matters website were also covered in a very helpful 1-hour NZIPIM webinar with Simon Petrie from Te Uru Rākau on 3 August 2021. You can read the written answers to questions asked during the NZIPIM webinar in this PDF [PDF, 225 KB] .

Farm Forestry New Zealand also has several good resources on integrating trees into a farming landscape.

Case studies

-

Rick Burke and Jan Loney, Bay of Plenty

Rick and Jan have been working hard to improve their sheep and beef farm's impact on freshwater and biodiversity, and are now turning their attention to the climate.

-

Anders & Emily Crofoot, Wairarapa

When New Yorkers Anders & Emily Crofoot took over Castlepoint Station on the eastern Wairarapa coast in 1998, they had to make some big adjustments, quickly.