Government and climate change

The Government is taking active steps to move New Zealand towards lower greenhouse gas emissions and greater resilience to a changing climate. This includes international and domestic reduction targets, a Climate Change Commission, changes to the Emissions Trading Scheme and developing a system to price agricultural greenhouse gas emissions.

International commitments

The Paris Agreement is the latest global agreement on climate change. It was adopted under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in December 2015 and commits all participating countries to act on climate change.

The Paris Agreement aims to:

- Keep the increase in global average temperature well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, while pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C

- Strengthen the ability of countries to deal with the impacts of climate change

- Make sure that financial flows support the development of low-carbon and climate-resilient economies.

New Zealand is a signatory to the Paris Agreement, which commits us to:

- Setting and regularly updating a domestic emissions reduction target (also known as a ‘Nationally Determined Contribution’ or NDC)

- Continuing to report on our emissions and on progress towards meeting our target

- Planning for adaptation to a changing climate

- Continuing to provide financial support to assist developing countries' mitigation and adaptation efforts.

Under the Paris Agreement, New Zealand has committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 50% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Domestic commitments

A credible, long-term greenhouse gas emissions reduction target is an important part of ensuring that New Zealand can meet its international commitments and make a smooth transition to a low emissions future.

This is achieved through the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019 (also known as the Zero Carbon Act), which was passed into law in 2019. It provides a framework for New Zealand to:

- Contribute to the global effort under the Paris Agreement; and

- Prepare for, and adapt to, the effects of climate change.

The legislation puts in place long-term targets for reducing New Zealand's greenhouse gas emissions:

- Carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide (the 'long-lived' gases) are to reduce to net zero by 2050

- Methane emissions are to reduce to 10% below 2017 levels by 2030, and 24-47% below 2017 levels by 2050.

This is the first time there have been different targets for different gases in New Zealand, recognising the different warming effect of methane in the atmosphere.

The legislation also introduced a series of emissions 'budgets' to act as stepping-stones toward the 2050 targets. An emissions budget is a set quantity of emissions allowed during a defined period of time. The climate change legislation requires each emissions budget to cover five years, except for the first budget which covers the period 2022-2025. Three budgets must be in place at any one time.

The legislation established a Climate Change Commission (see below) to advise the Government on those emissions budgets. It also requires the Government to have an Emissions Reduction Plan that describes how New Zealand will meet the emissions budgets and make progress towards the 2050 targets. The legislation also puts in place specific requirements for the Government on adaptation.

The Government's first Emissions Reduction Plan was launched in May 2022 and sets out emissions budgets out to 2035. You can find more information here. The Government also announced a package of funding to support the initiatives in the Emissions Reduction Plan.

Climate Change Commission

As noted above, the Climate Change Commission - He Pou a Rangi - was established in November 2019. Its purpose is to provide independent, evidence-based advice to successive governments on New Zealand's greenhouse gas emissions and the potential impacts and effects of climate change. It also monitors and reviews progress towards the country's goals for reducing emissions and adapting to a changing climate.

One of its early pieces of work was to develop a package of advice for the Government on:

- The first three emissions budgets covering 2022-2035

- The direction for the Government's Emissions Reduction Plan

The package also included advice on two other questions specifically requested by the Minister of Climate Change: (i) whether New Zealand's current Nationally Determined Contribution under the UN Paris Agreement is compatible with contributing to global efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels; and (ii) whether further reductions in biogenic methane might be required by New Zealand as part of those global efforts.

The Commission's advice was released in June 2021, following extensive public consultation. The Government then released its Emissions Reduction Plan in May 2022.

Emissions Trading Scheme

The Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is the Government's main tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in New Zealand and was established in 2008.

The ETS puts a price on greenhouse gas emissions, creating a financial incentive for businesses to reduce their emissions and landowners to earn money by planting forests that absorb carbon dioxide as the trees grow.

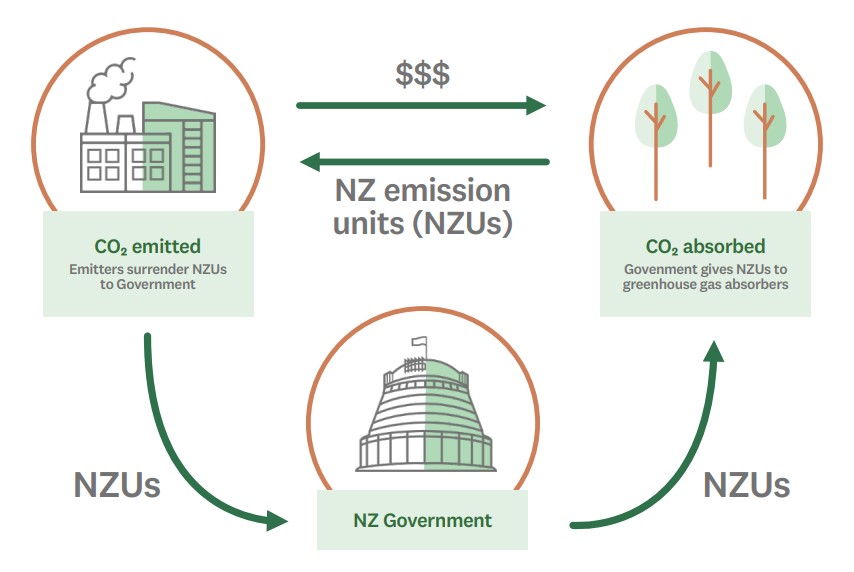

One emission unit, known as a New Zealand Unit or ‘NZU’, represents one metric tonne of carbon dioxide.

The Government provides NZUs to eligible foresters for carbon dioxide that is absorbed by their trees. The foresters can then sell these NZUs on the ETS market. Emitters (businesses with legal ‘surrender obligations’) must purchase enough NZUs to cover their emissions. These NZUs are then surrendered to the Government. It's up to the emitter to decide whether they reduce their emissions or purchase NZUs. The price the emitter pays for NZUs (also known as the carbon price) is set by supply and demand.

How the ETS works

The ETS was intended to be an 'all sectors, all gases' scheme. However, agriculture is not included other than for reporting purposes. This means carbon dioxide is the only gas currently priced.

The ETS was reformed in 2020, via the Climate Change Response (Emissions Trading Reform) Amendment Act, to improve its effectiveness. The following changes were introduced:

- A cap on total emissions covered by the scheme that declines over time, in line with the 5-yearly emissions budgets and the 2050 targets

- Auctioning introduced from 2021 to allow the Government to sell NZUs from within the cap

- Establishment of controls to prevent unacceptably high or low prices

- Price floor of $20/NZU, which will increase by 2% for each subsequent year.

- Cost containment reserve triggered if the unit price reaches $50, which would release more NZUs into an auction to ease demand. This will increase by 2% for each subsequent year, based on forecast annual inflation.

- Phase-out of industrial allocation from 2021 at a rate of 1% per year until 2030, 2% per year from 2030-2040, and 3% per year from 2040-2050

- Changes to improve forestry's participation

For more information on the ETS, see the Ministry for the Environment website or the Ministry for Primary Industries website. You can also watch this video explaining the NZ ETS, produced by the Ministry for the Environment.

Pricing agricultural emissions

Although agricultural greenhouse gas emissions are not included in the ETS, they are included in New Zealand's 2050 climate change targets, so a mechanism is needed to ensure reductions can be achieved.

In 2019, He Waka Eke Noa was formed to design a practical and effective system for reducing emissions at the farm level, as an alternative to the agriculture entering the ETS. He Waka Eke Noa - the Primary Sector Climate Action Partnership - comprises industry, government and iwi/Māori entities.

In June 2022, following months of development work and consultation on a range of pricing options, the He Waka Eke Noa partnership recommended to Government that a farm-level, split-gas levy be used to price emissions from 2025 instead of the ETS. You can read the He Waka Eke Noa proposal here. In summary, the partnership recommended the following:

- Emissions calculated and paid for at the farm level.

- Split-gas approach applies different levy rates to short- and long-lived gas emissions.

- Pricing starts from 1 July 2025 with a simplified levy system, moving to a full farm-level levy in 2027.

- Farmers calculate their short- and long-lived gas emissions through a centralised calculator (or through existing tools/software that are linked to the calculator).

- Incentive payments for reduced emissions from on-farm efficiencies and mitigations as technologies and practices become available.

- Incentives are provided for uptake of actions (practices and technologies) to reduce emissions

- On-farm sequestration is recognised, which could offset the cost of the emissions levy.

- Levy revenue is invested in research, development and extension, including a dedicated fund for Māori landowners

- A System Oversight Board with expertise and representation from the primary sector board would work closely an independent Māori Board to advise Ministers on levy rates and set the strategy for use of levy revenue.

Participants in the scheme would be GST registered and annually average over any of the following:

- 550 stock units (including sheep, cattle, deer, goats)

- 50 dairy cattle

- 700 swine (farrow to finish)

- 50,000 poultry

- Or apply over 40 tonnes nitrogen through synthetic nitrogen fertiliser

In addition to the He Waka Eke Noa partnership proposal, the Government sought advice from the Climate Change Commission. The Commission looked at whether farmers would be 'ready' to face a price on agricultural emissions from 2025 and agreed that they would. It also agreed that the best way forward was via a farm-level levy rather than in the ETS. However, there were a few key differences with the He Waka Eke Noa proposal:

- Nitrous oxide emissions from synthetic nitrogen fertiliser should be included in the ETS as soon as possible, and at the processor level not the farm level.

- Sequestration should not be included in the farm-level levy and instead should be handled in a separate system that could recognise and reward for other benefits such as biodiversity and freshwater.

The Government ran a public consultation on its preferred options for pricing in October/November 2022. It then released its high-level decisions in December 2022, which included:

- A farm-level split-gas levy for agricultural emissions that would price emissions from methane and nitrous oxide (including from fertiliser) from January 2025 (this date may be adjusted to later in 2025 to better align with farm accounting systems).

- Note that carbon dioxide emissions from fertiliser are not included (they had been previously included in the He Waka Eke Noa proposal

- Emissions thresholds set to determine participation in the scheme (equivalent to ~200 tonnes CO2-e per year):

- 550 stock units (sheep, cattle, deer, calculated on a weighted annual average basis); or

- 50 dairy cattle; or

- Applying over 40 tonnes of nitrogen through fertiliser.

- Reporting can be done at either the individual farm level or via a collective. If the latter, they would still need to be a GST-registered, legally recognised entity.

- A five-year price pathway for both methane and nitrous oxide would be established from 2025, providing certainty out to 2030. This would be reviewed after three years.

- Emissions levy to be set at the lowest price possible to achieve outcomes, with the revenue raised used to incentivise behaviour change.

- Incentive payments would be used to make the uptake of mitigation technologies and practices more cost-effective.

- Sequestration payments for eligible on-farm vegetation will also be an interim part of the farm-level pricing scheme until such time that further vegetation categories can be included in the National Inventory and ETS.

- Oversight of the pricing system would include the Commission and an Oversight Board with representation from the agriculture sector and Māori.

- Ministers would be responsible for setting and updating the levy prices.

Final decisions on the details of the pricing scheme were due to be made in early 2023, including the introduction of supporting legislation, but as yet there has been nothing released.

Published: June 20, 2023