Methane belched out by ruminant animals is responsible for 71% of our total agricultural emissions. Reducing methane is essential if New Zealand is to meet its national and international targets.

Actions to reduce methane

-

Stocking rate and performance

Modelling shows it might be possible to reduce total greenhouse gas emissions by up to 10% on some farms, by fine-tuning production systems so the same output is obtained from fewer animals.

-

Efficiency improvements

Increasing outputs relative to inputs won't necessarily reduce absolute emissions, but it will improve emissions per unit of product. It's been of great benefit to New Zealand already - and that's likely to continue.

-

Low-emission feeds

Some supplementary feeds reduce methane emissions per unit of feed intake, while others help reduce nitrous oxide emissions by decreasing the amount of nitrogen excreted onto pastures.

-

Once-a-day milking

Making a deliberate decision to milk only once a day throughout lactation can, under the right circumstances, reduce emissions and maintain profitability.

-

Potential actions

Some practices and technologies have been promoted as options to reduce emissions, but research is ongoing to get them into the national greenhouse gas inventory and/or fully demonstrate their efficacy on farm.

Where does methane come from?

Methane has several sources, including wetlands, landfills, forest fires, agriculture and fossil fuel extraction. In New Zealand, the largest proportion by far is belched out by livestock.

Ruminants such as cows, sheep, deer and goats have four-chambered stomachs, enabling them to readily break down and extract energy and nutrients from fibrous plants like grass. Microbes in the rumen break down complex carbohydrates into simpler molecules—a process known as enteric fermentation. Some of these microbes produce methane, which the animal then mostly burps out.

What influences how much methane an animal produces?

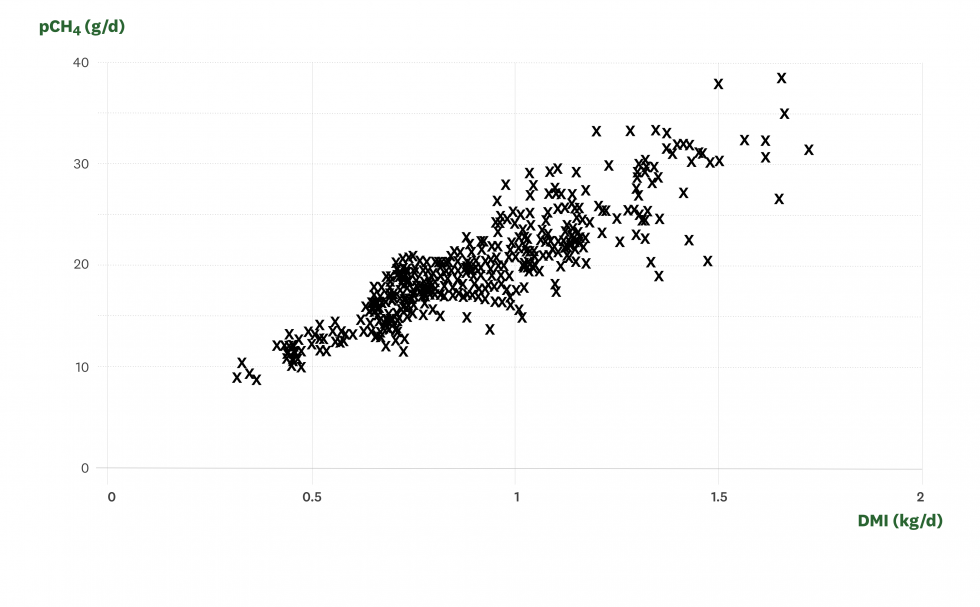

The amount of methane produced by an individual ruminant animal is directly linked to how much it eats, as shown in the graph below:

New Zealand studies indicate that approximately 21-22 grams of methane are produced per kilogram of dry matter eaten. This varies only slightly across the typical feeds in New Zealand’s pastoral systems: fresh pasture (rye grass and clover), pasture silage and maize silage.

The average dairy cattle beast produces approximately 98kg of methane per year, the average beef cattle beast produces approximately 61kg per year, the average deer approximately 25kg per year, and the average sheep approximately 13kg per year.

As highlighted at the top of this page, there are several actions that can be taken now to help reduce methane emissions at the farm level. You can click or tap on those actions to read more.

There is also considerable research underway looking at new approaches. You can read more on the Future actions page.

This video also gives a helpful overview.

Is methane really an issue?

In short, yes. Scientists estimate that methane emissions are responsible for almost 40% of the total warming effect generated by human activities so far.

Carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide are long-lived gases. Nitrous oxide stays in the atmosphere for centuries, and carbon dioxide for millennia. Therefore, every unit emitted today increases their concentration in the atmosphere and adds to the warming caused by past emissions. By comparison, methane is a relatively short-lived gas—virtually all of the methane emitted today disappears within about 50 years. So new methane emissions today replace, rather than add to, previous methane emissions.

However, while methane is up there, it's much more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide. Averaged over 100 years, one tonne of methane causes about 30 times the warming as one tonne of carbon dioxide. Some of the heat trapped by methane causes other changes in the global climate system as well, resulting in warming that extends beyond methane's relatively short lifetime in the atmosphere.

Because methane doesn’t accumulate in the atmosphere in the same way that carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide do, methane emissions don’t need to reduce to zero to stabilise the climate. But ongoing methane emissions keep Earth a lot warmer than it would be otherwise. Reductions will help slow climate change and are critical for keeping warming to well below 2°C (ideally 1.5°C) above pre-industrial levels. Reductions are also needed to meet New Zealand’s own greenhouse gas emissions targets, which for methane are:

- By 2030, methane must reduce to 10% below 2017 levels

- By 2050, methane must reduce to 24-47% below 2017 levels

For more on the targets, see the Government and climate change page.

Isn’t methane carbon neutral?

Many people ask whether methane is part of a 'carbon neutral cycle'; carbon in and carbon out meaning that it doesn't need to be reduced. Unfortunately, it's not as simple as that.

All carbon dioxide absorbed into grass and eaten by grazing animals eventually returns as carbon dioxide to the atmosphere and is therefore part of a closed carbon cycle. However, it is the conversion of some of the ingested carbon into methane that causes the challenge.

Methane contains the same amount of carbon as carbon dioxide but behaves very differently in the atmosphere—as described in the section above. So, while the cycle remains carbon neutral, it is not greenhouse gas or warming neutral.

See the NZAGRC website for more on how livestock affect the carbon cycle.

Other helpful resources

For more on methane:

- Read this technical report on New Zealand's methane emissions from livestock, commissioned by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (PCE), and another PCE report on Understanding the biological greenhouse gases

- Check out how methane from livestock contributes to climate change in this diagram [PDF, 169 KB] by the Ministry for the Environment.

- Read information on methane from the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre (NZAGRC)

- Farmers Weekly article 29.07.19: The methane problem [PDF, 115 KB]

- Information on methane from the Australian Academy of Science