Ben Troughton, Waikato

Waikato dairy farmer Ben Troughton is on a journey from a high input, high output operation towards a smaller, more diversified and environmentally sustainable system. It’s a slow journey but the benefits for the soil, livestock and the environment are starting to show.

About the farm

Ben Troughton’s connection to the dairy farm he manages near Matamata in the Waikato runs deep. Grandfather Vic bought the property nearly 100 years ago, and bloodlines in Ben’s current milking herd trace all the way back to Vic’s original animals.

And it’s the farming principles that Vic lived by – keeping it simple and local, and looking after the land, livestock and each other – that Ben is now looking to emulate as they strive for a more sustainable and fulfilling business.

Ben share milks 500 cows on his family’s 200-hectare property. Soils on the farm are silt loams ranging from poor to well-drained, and the average annual rainfall is 1,210mm. Ben runs this as a System 2 operation, with a stocking rate in 2019/20 of 2.23/ha.

Environmental focus

When Ben took over the farm, all the advice he was receiving at the time pointed to increasing inputs: higher stocking rates, more imported feeds, more nitrogen fertiliser, more pressure to produce. He saw the effect it was having on the health of his cows, on staff, and on the environment, and decided that it just wasn’t for him.

More sustainable practices have been incorporated slowly over the last ten years and underpinned by development of a farm plan, a process Ben says is well worth the time and effort.

Change began with a close look at stocking rates. Ben has managed to reduce them from 3.53/ha in 2011/12 to 2.23 in 2019/20, with total stock numbers dropping from 700 to 500 and a corresponding increase in per animal production achieved. Split calving in autumn and spring was also introduced as well as a shift to year-round once-a-day milking. Ben estimates that production dropped by about 7% but that was outweighed by the fact that his cows and their calves are healthier and there are lower breeding costs and vet bills.

Ben also reviewed nitrogen fertiliser use, aiming to reduce leaching and surplus nitrogen. Urea inputs have since been reduced to about 10% of what they were (10-30kg N/ha applied in the three years since 2019) and he’s almost ready to eliminate artificial nitrogen inputs altogether. Other changes have been introduced like establishing a feed pad, improving effluent management, minimising tillage, riparian planting along all the drains and incorporating plantain into their grass seed mixes.

All of this has been aimed at reducing the farm’s environmental impact and removing stress on animals. An improved work-life balance has also been a welcome side-effect.

Ben’s focus on low-input farming might not work for everyone. But – looking back – he wouldn’t have it any other way.

Greenhouse gas numbers

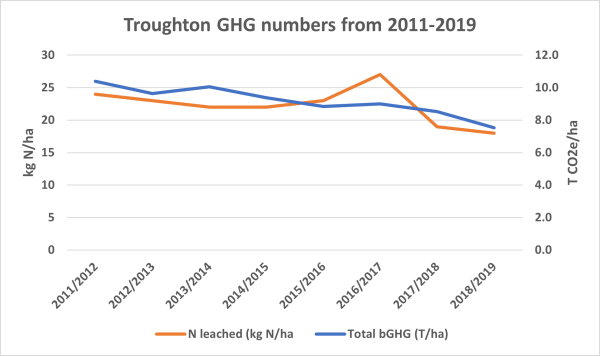

When Ben started on this journey, he wasn’t doing it for the climate – but his numbers show just what an impact he’s had.

Ben has reduced his total greenhouse gas emissions per hectare (methane and nitrous oxide) by nearly a third since 2011. At the same time, he’s reduced his nitrogen leaching by a quarter but his productivity per animal (kg MS/cow) has gone up by nearly a third. This is an incredible achievement and proof that it is possible to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and remain profitable.

Ben has had help to figure out his greenhouse gas emissions through a partnership with the University of Waikato where his farm is part of a research and monitoring programme. He also has an Overseer file, which gives him access to greenhouse gas data and he receives regular reporting as a Fonterra supplier.

To find out more about the tools for estimating on-farm greenhouse gas emissions, see our Know Your Numbers page.

On-farm actions

As mentioned earlier, Ben has implemented a range of changes on his farm to improve his environmental impact. Many of these have helped reduce his methane and nitrous oxide emissions:

- Reducing stocking rates and improving performance

- Efficiency improvements

- Reducing nitrogen fertiliser

- Once-a-day milking

To find out more about these actions and other ways to reduce on-farm emissions, see our Current actions page.

Know your numbers and have a plan

By now, all farmers and growers must have a record of their annual on-farm greenhouse gas emissions (methane and nitrous oxide). By the end of 2024, they'll also need to have a written plan in place to manage them. These requirements are part of the He Waka Eke Noa partnership and are intended to help get farmers ready for agricultural greenhouse gas emissions to be priced from 2025. To find out more on how to do this, see our Know Your Numbers page.