Phill and Jos Everest, Canterbury

A balanced approach to dairy farming on the heavy soils of coastal mid-Canterbury is essential in Phill and Jos Everest's efforts to reduce Flemington Farm's agricultural greenhouse gas emissions.

About the farm

Flemington Farm is about 10km south of Ashburton and 4km from the Ashburton River in mid-Canterbury, almost 280 hectares of flat irrigated land that was once part of the vast Longbeach estate. Phill and Jos have owned the farm for 33 years, though it was leased as a dry stock and cropping farm for 23 years while Phill built up his farm consultancy practice.

The land was converted to dairy production 10 years ago and carries a herd of 750 on 221 hectares; 38ha is used for winter/feed crops and some young stock and the balance, 18ha, is in laneways, buildings and trees.

Flemington Farm, near Ashburton (Photo: Dave Allen Photography)

The Everests operate a low-intensity system with a very efficient irrigation regime. The farm’s soils are heavy with a high water-holding capacity. Irrigation water is supplied from two bores (50-60m deep), with three centre pivots covering most of the property.

The farm is run as a System 2/3 with very little feed imported to milking cows. Pasture comprises approximately 84% of the cows’ intake, with 5% supplement fed to milking cows and 11% from wintering off. No cows are wintered on the milking platform and young stock are grazed off from weaning.

The Everests supply to Synlait and are part of their Lead with Pride scheme, which recognises and rewards suppliers for achieving dairy farming best practice. Phill is also one of DairyNZ's Climate Change Ambassadors and has been involved in the DairyNZ 'Meeting a Sustainable Future' initiative in the Selwyn and Hinds catchments.

In Phill's words, "we're just trying to do the best we can for the environment and the cows and the people on our farm".

Getting to grips with greenhouse gas emissions

Having a farm plan has been a critical part of Phill and Jos' journey, allowing them to meet the increasingly stringent environmental obligations necessary for the catchment while still running a resilient and profitable business. The farm plan is also a requirement of supplying to Synlait, whose Lead With Pride programme requires excellence across four 'pillars' of the environment, milk quality, animal health and social responsibility (people).

An increasing part of the Everest's environmental focus is climate change. A farm's greenhouse gas emissions comprise methane, largely from livestock burping with a small amount from manure management, and nitrous oxide which occurs when microbes in the soil act on the nitrogen in animal dung and urine and in fertiliser.

The Everests use OverseerFM to get their greenhouse gas numbers. They also receive a summary and benchmark report from Synlait, who also provide templates and tools to help Synlait farmers identify potential actions for reducing their emissions.

"The Synlait checklist we're working to is really valuable in terms of how you think about and approach your actions on-farm and how they affect greenhouse gas emissions," says Phill.

Dairy farmers can also get their greenhouse gas numbers from a range of other sources. DairyNZ also has a handy calculator to help a farmer work out whether their business and farm system are 'future ready'. This calculator provides:

- Operating profit per hectare

- Debt to asset ratio

- Tonnes of methane emissions per hectare (does not provide nitrous oxide)

- Purchased N surplus per hectare

Phill and Jos' greenhouse gas numbers

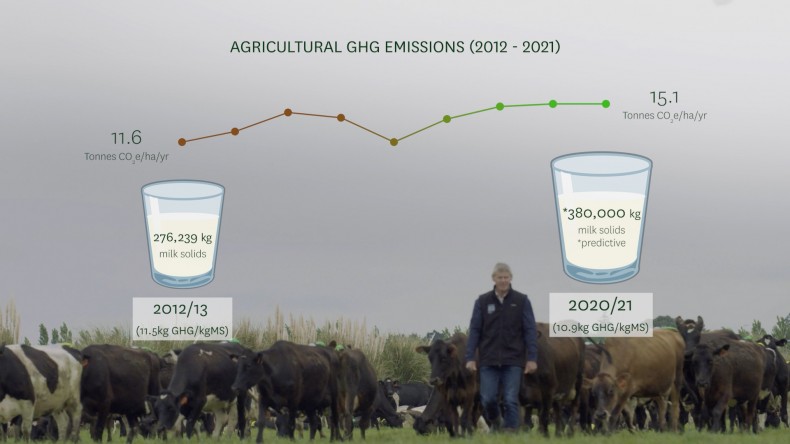

Flemington Farm currently generates about 15.2 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per hectare. That's about 4.4 tonnes per cow and about 8.9 kilograms per kilogram of milk solids produced. The figure below show's the farm's emissions from 2012 to 2021.

Agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and milk solids production on Flemington Farm, 2012-2021

Since converting to dairy over 10 years ago, the Everest's agricultural greenhouse gas emissions actually increased as they developed the farm and made it profitable. Since then, they've put a plan in place to reduce emissions, which have stabilised in recent years, even though production has increased. It hasn't always been an easy journey, but it's a promising sign that Phill and Jos' mitigation plan is starting to make a difference.

On-farm actions

By working out their agricultural greenhouse gas numbers and developing a plan to reduce them, Phill and Jos are well on their way to preparing their farm system for the demands of the future.

"Over the past 10 years, the focus has been to get the farm up and cranking," says Phill. "In terms of reducing emissions, we're doing a lot of small things that might seem to have a small impact, but cumulatively we're starting to make progress."

Phill's plan spans a 2-5 year period, meaning he can adjust as conditions and priorities change along the way. Right now, he and Jos are working on:

- Reducing use of nitrogen fertiliser (aiming to get down to 190kg/ha by June 2021) and carefully managing what is applied, where and when

- Using a coated urea to reduce nitrogen loss

- Carefully managing how effluent is spread through the irrigation system to optimise its fertiliser contribution to the farm

- Making ongoing genetic improvements to produce the same amount of milk from fewer animals

Genetics at work at Flemington Farm (Photo: Dave Allen Photography)

- Feeding low-protein fodder beet in the autumn to lower protein intake and consequent nitrogen loss, and to precondition cows before going away for winter grazing

- Including plantain, chicory and clover seed each year in maintenance fertiliser dressings to maintain a higher percentage in the sward to address nitrogen loss

- Planting the farm's main drains and boundaries to help improve waterways, act as a carbon sink and provide shade for stock (just under 10,000 trees and plants have gone in so far).

"The environment is hugely important to us," says Phill. "We're prepared to give things a go and we're seeing some encouraging signs."

Visit our Current actions page for more information on how these things can help reduce methane and nitrous oxide emissions. You can also read more about Phill and Jos' work to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and their nitrogen leaching in this DairyNZ case study, put together in early 2021 as part of a Greenhouse Gas Partnership Farms Project.

Know your numbers and have a plan

By now, all farmers and growers must have a record of their annual on-farm greenhouse gas emissions (methane and nitrous oxide). By the end of 2024, they'll also need to have a written plan in place to manage them. These requirements are part of the He Waka Eke Noa partnership and are intended to help get farmers ready for agricultural greenhouse gas emissions to be priced from 2025. To find out more on how to do this, see our Know Your Numbers page.